As I walk around my West End neighbourhood here in Vancouver, I see some little evergreens planted between the sidewalk and the road. They remind me of the trees of Christmases past.

Growing up in post-war Wales, I became used to Christmas trees that were no more than, perhaps, five feet tall. Always with a mindset of making things for ourselves, our family would sit at the kitchen table and cut sheets of red, white, and green paper into long strips. We would paste these together into chains to festoon around the tree’s branches. We would save all the silver foil milk bottle caps that came each day on top of the milk. Washed clean of cream (cream always rises to the top) and reshaped, each one became a small shiny bell to hang on the tree. Sometimes we stitched three together in a chain. Very festive. We would buy a package of tinsel. Each piece was thick and heavy. We hung them singly all over the tree until it sparkled.

We didn’t need electric lights or candles, and I don’t remember any store-bought baubles. The preparation was the best part. Mum kept a star from one year to the next to go on the top. A Christmas treasure! She also made something resembling poinsettias out of red crêpe paper and ivy, using her creative skills.

Now that I am a tree enthusiast, I wonder what the evergreen tree species was that we used each Christmas in Wales. Dad bought whatever was for sale. It was the same species each year—pyramidal in shape so its apex could support the star. Were its needles sharp for a child’s fingers? Maybe. So, was it a spruce tree, perhaps a Norway spruce, with its stiff, sharp needles? That was the most popular Christmas tree species when I was growing up, decades ago. Our trees always had branches that grew out strongly to display the tinsel and milk bottle cap bells the best!

These three photos of a mature Norway spruce show (1) the stiff sharp needles, (2) a seed cone (on the left) and pollen cones (on the right), and (3) the bark and trunk

When I emigrated from Wales to Canada and lived on a ranch not long after, I was astonished that we could drive out to the forest a week before Christmas and cut down our very own tree. What a rich aroma of the forest wafted throughout our home then. I expect they were Douglas-firs (Pseudotsuga menziesii), not actually firs at all.

These five photos taken of different Douglas-fir trees show (4) the gentle needles growing around the stem like a bottle brush; (5) pale green immature seed cones and one dry, year-old seed cone; (6) several seed cones in late September; (7) bark; (8) bole; and a ninety-year-old Douglas-fir in Stanley Park.

For a handful of years in the Eighties I lived in Australia. There, we used different evergreens—eucalyptus trees. And never the whole tree. Just a branch or two. And on Boxing Day, we wouldn’t go to the shops in our winter jackets, we’d go to the beach with our swimsuits and towels, and swim in the ocean because summer had begun. Santa Claus in shorts! Just imagine.

These days, we have a plastic tree and we hang it with electric lights. There’s no smell of Christmas and no real needles that have to be swept up each morning. How times change.

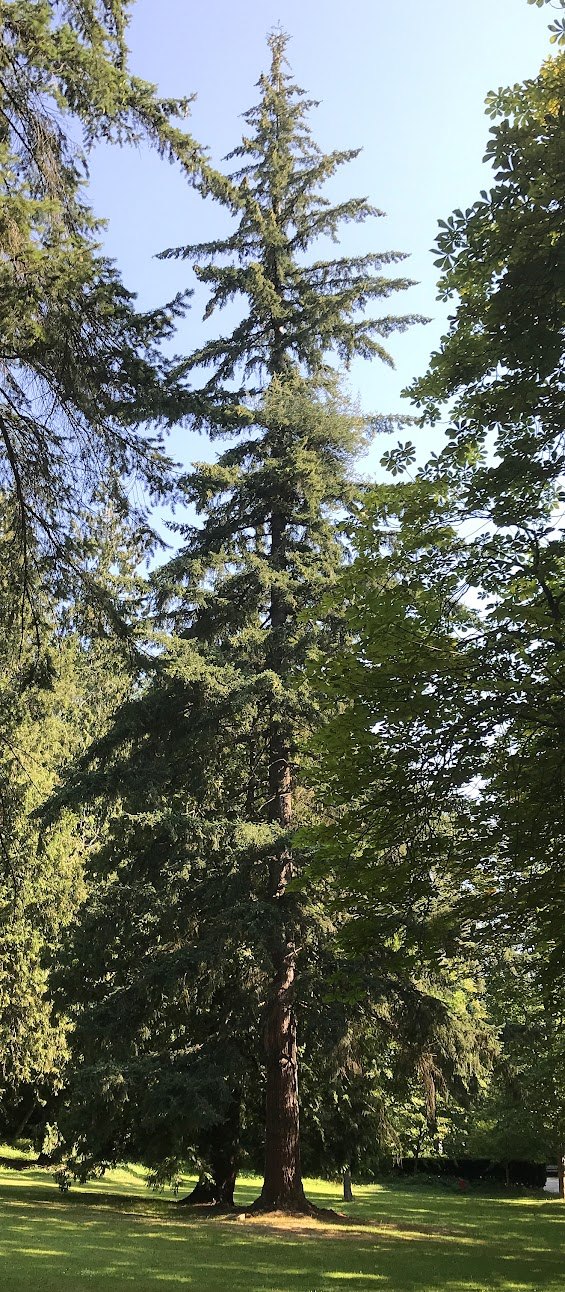

At the end of November I was walking in VanDusen Botanical Garden when I came across the tree that, in the UK anyhow, has taken over the live Christmas tree market now in 2021. It’s a Caucasian fir, an Abies nordmanniana. Planted in 1973, it is 48 years old. Just a youngster. This species has plump needles that are rounded on the ends, a perfect Christmas tree for kids to decorate.

Caucasian fir’s other common name is Nordmann fir, in honour of Finnish professor of zoology and botany in Russia, Alexander von Nordmann (180366). He discovered it growing in its native habitat on an 1836 expedition to the Caucasus Mountains, a range that stretches from the Black Sea in the west to the Caspian Sea in the east.

Caucasian fir is a true fir, an Abies, unlike a Douglas-fir, a Pseudotsuga. What are the differences between a Douglas-fir and a Caucasian fir? Quite a few, it turns out—the height, the fullness of the foliage, the final tree shape, the arrangement of branches on the tree trunk, the bark, the needles and their arrangement on a branch, and the seed cones. The photos show some of these differences.

True firs takes several years to mature by which time they are quite tall. Because seed cones on a fir grow upright in the uppermost branches and because their the cones disintegrate slowly in place we never see a true fir cone whole on the ground. All we ever see are the cone scales, some with the seeds still attached (see photo 13).

Our daughter and our three Jewish grandchildren will be joining us for dinner on Christmas Day this year. We won’t be making any decorations for our artificial tree, but we are all looking forward to watching the children decorate our little tree with the ornaments we’ve been collecting for decades.

These seven photos of the Caucasian fir planted in 1973 in VanDusen Botanical Garden show (10) a branch hanging low to the ground, (11 and 12) stems with plump, blunt needles and many light brown pollen cones, (13) fir cone scales, one pair holding seeds, (14 and 15) views of the fir, and (16) the dark trunk that’s in shadow from all the low hanging branches.

Nina S., Vancouver Master Gardener