April 5: Today I notice that Douglas-fir evergreens have been freckled yellow with pollen cones for a while, probably since early to mid-March. Usually the lowest branches of a Douglas-fir are so high off the ground that it’s impossible to see these male cones up close. I am walking through a small new-to-me park: Ebisu Park at Marpole, Vancouver. (Ebisu is one of several Japanese gods of good luck, and the patron of fishermen, tradesmen, and children. Japanese fishermen were very active in the salmon fisheries along the whole stretch of the Fraser River from the late 1800s on.1)

A Douglas-fir growing near a fence in Ebisu Park has lowered its branches to where I can see the tree is covered in pollen cones.

Out comes my camera.

I’ve never seen these tiny male cones before. Perhaps they are usually too far away. On high branches. Or I don’t notice them. Each one is as small as my pinky fingernail and some are ripe, clearly ready for their pollen to blow onto the invisible female Douglas-fir seed cones and pollinate the seeds. Where are those immature seed cones? I look closely. I don’t see any. I’ll have to wait.

For me, Douglas-fir is a trickster, growing differently depending on its soil, its wind and water, its woody companions, and the weather. Sometimes, its spirally arranged needles make each green branch look like a functional bottle brush and the tree looks abundant. At those times, each of the blunt-tipped, flat needles is around 30 mm long. At other times, the needles are so short (no more than 15 mm long), sparse, and thin that the tree looks straggly and barely recognizable. These trees are growing in poorer soil.

In a forest, this very tall native evergreen can grow to a considerable height and girth, up to 90 m tall with a diameter of up to 3 m. Each tree, rubbing up against its neighbours, loses its lower branches through self-pruning; the branch architecture is asymmetrical as the tree ages (a very recognizable feature); its bark is uniquely grooved, vertically; and its 8 cm to 10 cm long seed cones with their three-pointed bracts—one long point and two shorter ones—hang prolifically on the tree and fall whole on the ground.

I think of the First Nations myth about a Douglas-fir cone’s bracts resembling the rear end of a hiding mouse. The grooves on Douglas-fir’s bark are deep enough to afford a tiny mammal a place to hide from a forest fire. Indeed this thick, corky covering protects Douglas-firs from fire, while also benefitting their fallen cones by providing a clearing in which they can germinate.

April 15: Ten days later, I look for female cones on another Douglas-fir with low-hanging branches. This tree grows west of the hedge surrounding Brockton Oval in Stanley Park. Several female cones are taking shape; they are a mixture of light pink and spring green. Only the bracts are apparent so far; the cone scales will grow later. These young cones are growing erect in order to be wind-pollinated.

April 23: Beside the Dr. Cheung-Kok Choi Memorial Bell in the grounds of the Asian Centre at the University of British Columbia grows another low branching Douglas-fir. Among its myriad of pollen cones is one erect seed cone. Just one.

May 19: Now, three-and-a-half weeks since I was last in the grounds of the Asian Centre, I check out the low-hanging branches of the Douglas-fir again. There are many more female cones now and they are bigger. These must already be pollinated, because they are starting to hang down.

How thrilled the early explorers who came to our West Coast of North America must have been to discover an evergreen so tall, so straight, and so true. In 1792, Archibald Menzies was hired as the surgeon, botanist, and naturalist on Captain George Vancouver’s voyage to North America on HMS Discovery.

Born in Perthshire, Scotland, Menzies had trained as a botanist at Edinburgh University. His role was to preserve such new plants as were worthy of a place among “His Majesty’s very valuable collection of exotics at Kew.”2 Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) gets its species name from Archibald Menzies.

Archibald Menzies briefly mentored a young man, David Douglas, also from Perthshire in Scotland. Douglas trained at Glasgow University as a botanist and gardener. He explored the Scottish highlands and then North America in the 1820s. He was the botanist responsible for encouraging the commercial use of the Douglas-fir, writing about it in his journal: “The wood may be found very useful for a variety of domestic purposes: the young slender ones exceedingly well adapted for making ladders and scaffold poles, not being liable to cast; the larger timber for more important purposes; while at the same time the rosin may be found deserving attention.”3

In 1834 in Hawaii, David Douglas died a mysterious and brutal death. He was only 35. He was last seen at the hut of Englishman Edward “Ned” Gurney, a bullock hunter and escaped convict. Douglas apparently fell into a pit trap where he was crushed by a wild Hawaiian bull that fell into the same trap. However, Gurney was also suspected in Douglas’s death, as Douglas was said to have been carrying more money than Gurney subsequently delivered with the body.4

Douglas-fir, this evergreen that is native to North America’s West Coast, China, and Japan, celebrates both Menzies and Douglas: Menzies in the specific epithet of its Latin name of Pseudotsuga menziesii; Douglas in its common name of Douglas-fir.

We owe the usage of fir in this tree’s common name to the desire of those who colonized our West Coast to simplify tree names to ones they recognized. And they were familiar with firs in their native lands. But Douglas-fir is not a member of the fir genus of Abies; hence the hyphenation.

Sticking to the topic of this tree’s binomial nomenclature—its two-part Latin name—Douglas-fir went through a series of names from when Archibald Menzies first discovered its uniqueness to decades after Douglas recognized its potential. The route to this Latin name was circuitous, but it was finally pinned down in 1867 by the French botanist and conifer expert, Élie-Abel Carrière, who first created the genus Tsuga, meaning “hemlock” and then created the genus Pseudotsuga, meaning “false hemlock.”5 He recognized some of the similarities between Douglas-firs and hemlocks, such as flat needles and seed cones that stay whole when they fall to the ground (unlike the seed cones of every true fir tree in the genus, Abies, which disintegrate as they mature, a cone scale at a time).

For a while after 1867, Douglas-fir was known as Pseudotsuga taxifolia, recognizing how Douglas-fir needles are similar to the needles of a yew tree (Taxus genus). But Pseudotsuga menziesii was deemed the original name and thereby became the species’ legitimate Latin name.6

Sometimes, to differentiate it from the other geographic race growing in North America, the coastal Douglas-fir is identified as Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii.

Walking through UBC campus one day, I came across a couple of young evergreens that were blue in colour. The cones were familiar, almost a caricature of the Douglas-fir cone I knew, because the bracts flared out from the cone. I finally realized these were Rocky Mountain Douglas-fir trees with the Latin name, Pseudotsuga menziesii var. glauca, where glauca is Latin for the adjective glaucous, meaning both bluish-white in colour and covered with a waxy coating that rubs off.

This race of Douglas-fir grows more slowly to half the height and girth of its coastal cousin.7

I recognize that this study of nomenclature—sorting plants out by their taxonomy—brings together my love of botany and trees and their history, both native and ornamental.

Vancouver’s history is closely connected with the abundant wealth of the Douglas-firs that were growing here when European settlers first called Gastown home. For over a hundred years starting around 1860, Douglas-fir was felled for its prized timber, the broad boles going for masts for ships. The first settlement of Gastown became the more established Granville and then it incorporated as the City of Vancouver in April 1886.8 Much of this was on the back of the Douglas-fir.

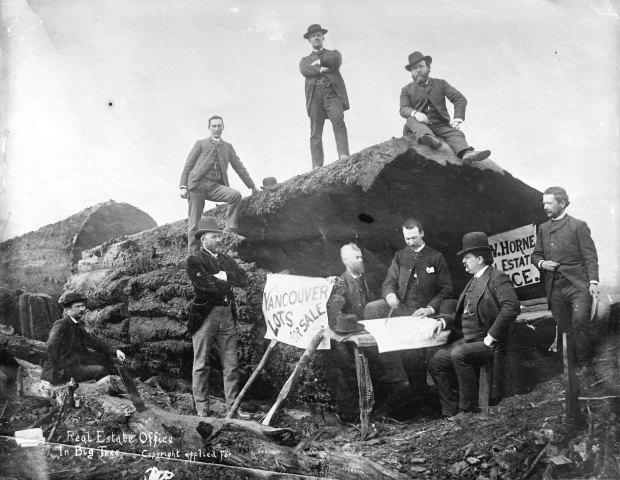

When a particularly large Douglas-fir fell in the middle of the new city the next month, May 1886, 8 James W. Horne, a landowner and realtor, used the huge tree to advertise the desirability of living in Vancouver: lots of good timber was to be had for building a home and for employment!

By mid-June, the female cones on Douglas-fir trees everywhere will have been pollinated and their posture will have changed from erect to pendulous. They will be long enough and plump enough to see, no matter how high up they hang. For the rest of the year they will continue to mature, dry out, and turn a darker brown. They will release their seeds from September through to the following spring, when the annual process starts all over again.

It’s been a joy to watch these cones grow from nothing (that I could see!) to 10 cm long this year. Take a look where you live. Douglas-firs are ubiquitous in Vancouver: on trails, in parks, and even in some yards. If the ground is covered with mature cones, the Douglas-fir won’t be far away.

Nina Shoroplova, Vancouver Master Gardener

1 https://covapp.vancouver.ca/ParkFinder/parkdetail.aspx?inparkid=236

2 Archibald Menzies, Menzies’ Journal of Vancouver’s Voyage: April to October 1972. Edited by C.F. Newcombe, MD. Victoria, BC: Legislative Assembly of British Columbia, 1923. open.library.ubc.ca/collections/bcbooks/items/1.0226118 and archive.org/details/menziesjournalof1792menz/

3 David Douglas, Journal Kept by David Douglas, 1823-1827. London: William, Wesley & Son, 1914; Biodiversity Heritage Library, 2006. www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/59487#page/5/mode/1up.

4 John Davies, Douglas of the Forests: The North American Journals of David Douglas. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1980.

5 https://www.conifers.org/topics/Botanists.php

6 F.A.S., “Pseudotsuga menziesii versus Pseudotsuga taxifolia,” Taxon 5, no 2 (April 1956): 38-39, www.iapt-taxon.org/historic/Congress/IBC_1959/pseudots_men02.pdf

7 James A. Young and Cheryl G. Young, Seeds of Woody Plants in North America. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1992. | Vancouver Trees App

8 Nina Shoroplova, Legacy of Trees: Purposeful Wandering in Vancouver’s Stanley Park. Victoria: Heritage House, 2020.